I cannot tell you how many emails I get from people fretting over their ketone levels. It’s time to set the record straight on this issue. I wish there was someplace I could refer people for reliable information on this subject, but I haven’t come across a blog post or podcast interview that explains things satisfactorily. At least, not to my satisfaction. And that is and always has been my goal in writing my blog: I explain things the way I would want someone to explain them to me, if I were new to all this. And since no one—as far as I know, anyway—has tackled this subject the way I would, I finally had to just sit down and write this. If you feel it’s educational, please share it in the low carb and/or ketogenic circles you frequent, because I know this issue comes up all the time in ketogenic forums and Facebook groups. (And if you know of other good resources on this topic, feel free to provide a link in the comments, and I’ll update this post to include it.)

There are few issues more controversial regarding ketogenic diets than whether you should measure your ketones. There are valid reasons to measure, but there are also a lot—a lot—of misconceptions about measuring ketones and how to interpret the data. So let’s get into when and why it’s a good idea to measure, who doesn’t need to measure, and most important, what the numbers mean. (I said who “doesn’t need to” measure rather than who shouldn’t measure because if you want to measure, then go ahead. There’s really no should or shouldn’t here. But if you choose to measure, you need to understand how to interpret and understand the numbers so you don’t jump to illogical and false conclusions.)

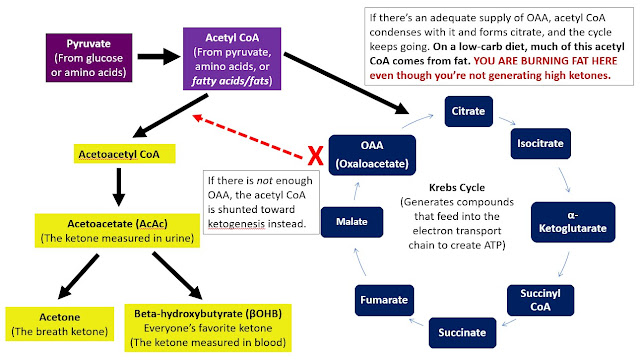

I will also be covering the difference between being fat adapted versus in ketosis. I tried to do it in a few posts awhile back, but I think I the way I explain it here is much better because I will show you the biochemical pathways involved so you will be able to see how it actually works. My hope is that this will go from a vague concept in your mind to, “Oh! NOW I get it!” And you will understand very clearly how you can absolutely, positively have a fat-based metabolism and lose body fat even if you’re not in ketosis.

Who Should Measure and Why

The first thing to ask yourself is why you are measuring.

This goes hand-in-hand with why you are following a ketogenic diet and what you’re looking to accomplish. Some goals might necessitate measuring ketones, while it’s a waste of money unimportant for others.

More and more people are experimenting with ketogenic diets as adjunct therapy for a number of issues, including migraines, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, cancer, diabetes (type 2 and type 1), PCOS, GERD, cardiovascular disease and more. Some of these conditions might be positively impacted only when ketone levels reach a certain threshold, while others might respond favorably to a general reduction in dietary carbohydrate load and inflammatory foods with no particular emphasis on staying in ketosis and no requirement to do so. If you’re using a ketogenic diet to help manage a specific condition, measuring ketones can give you information about how your ketone levels affect your signs and symptoms. You might discover that you need to stay above a certain level in order to notice improvement, and you might be able to identify particular foods or activities (e.g., fasting, exercise) that either help you do that or that take you further from that goal.

On the other hand, if you’re using a ketogenic diet primarily for fat loss, it’s not necessary to measure your ketones. Ketones are the result, not the cause, of breaking down fat. Having higher ketones doesn’t guarantee you’ll lose more body fat or lose it more quickly, so your ketone level tells you nothing about how effective your diet is for reaching that particular goal. Remember: ketones come from breaking down fat, which is great, but if your ketone level is high, you can’t be sure whether it’s from burning the fat on your body or from the fat on your plate. (Or in your fat-loaded coffee, if you’re into that.) A scale, not a ketone meter, is your best tool for gauging weight loss, and if you’re going for fat loss, a tape measure is even better. The knowledgeable people in the KetoGains community have a saying for fat loss: “Chase results, not ketones.”

It’s also not necessary to measure ketones if you’re using a low carb or ketogenic diet to deal with disorders related to insulin resistance, which include such diverse issues as PCOS, gout, hypertension, erectile dysfunction, benign prostate hyperplasia/hypertrophy (BPH), and possibly inner-ear and balance disorders, like vertigo, tinnitus, and Ménière’s disease. These conditions are driven primarily by chronic hyperinsulinemia, so the main thing that helps them is lowering insulin. Once more, for effect: what’s responsible for improvement in these conditions is the lowering of insulin, not the presence of ketones.

That being said, it’s not a terrible idea to measure ketones anyway, at least for a little while. You might find you have better energy, think more clearly, have no carb cravings, have a more positive and optimistic outlook, and just plain feel better when your ketone levels are higher, and you’ll only know if you measure. If you feel especially great at a particular moment, you can test to see if maybe your ketones are a bit higher than usual, and this would tell you that you, personally, feel your best when your ketones are on the high end of normal. And if that’s the case, then you can prioritize specific foods or behaviors that help you stay there. But you still wouldn’t have to measure forever. Once you identify what does and does not work for you, you’re good to go. (For a while, anyway. Things change over time.)

The second thing to keep in mind:

In their book, The Art and Science of Low Carbohydrate Living, prominent low carb and ketogenic researchers Jeff Volek, PhD, RD and Stephen Phinney, MD, PhD write that the range for nutritional ketosis is a blood level of beta-hydroxybutyrate (BOHB) of 0.5-5.0 mmol/L – a tenfold difference! You might feel beneficial effects of ketosis anywhere inside this range, so don’t be discouraged if your ketone level is relatively low. What matters is how you feel or whether your health condition is improving, not your ketone level.

People vary widely in their bodies’ tendency to produce higher ketones. Some people’s bodies simply generate ketones more readily than others’. Some people—usually young, athletic males—can generate a relatively large amount of ketones even while consuming more carbohydrate than would be considered a ketogenic diet level. (As Chris Masterjohn, PhD, said, “Pizza couldn’t kick me out of keto when I was in the gym all the time.”) Other people might have to fast, take MCT oil, or employ other measures to get to that same ketone level. Don’t compare your results to someone else’s, and don’t let anyone “ketone shame” you on social media. It’s not a contest or a race. Someone might feel like a total rock star with BOHB at “only” 0.6, while someone else might not notice any difference unless their ketones are above 2.0. It’s entirely individual and the only competition you’re in is to feel your best.

And a third thing: ketone levels fluctuate throughout the day.

So if you’re testing only once or even twice a day, you have a very limited view of what your body is doing all the rest of the time. (And considering the price of blood ketone test strips, most people don’t test blood ketones multiple times throughout the day. If you have a money tree in your backyard and want to test five times a day, I’ll kindly point you to the “donate” button on my blog, haha! Also, I’ve never been to Greece…) Most people find that urine ketones are highest in the morning and blood ketones are highest later in the day, but there’s individual variation with this.

Several things can affect ketone levels fairly quickly. For example, eating a fat-rich meal—especially if it contains MCT oil or coconut oil—can elevate ketones in short order. (In fact, MCT oil will do it even if you’re eating a lot of carbs, and obviously, so will exogenous ketones, which might be great as medical therapy, but which I do not recommend for fat loss, and which deserve their own post someday. Or you can just read Marty Kendall’s on this subject, which is fabulous.) Some people find that exercise raises ketones, and for many people, fasting will raise them too. Exogenous ketones in the form of ketone salts or esters will raise ketones, but using exogenous ketones doesn’t give you any insight into how your body produces its own ketones. (You could eat a bagel, take exogenous ketones and then, sure, you’ll see high ketones on your meter, but I don’t recommend this strategy.)

Measuring ketone levels can give you information about how your diet, sleep, stress levels, and exercise affect you. But don’t take the numbers at face value. It’s critically important that you understand how to interpret what you see, or you run the risk of coming to false conclusions—for example, that your ketone levels aren’t high enough, or that a certain food “kicked you out of ketosis.” Or maybe even more important, that you are somehow failing at your low carb or ketogenic diet because you rarely—if ever—see “high” levels (e.g., >2.0-3.0mmol/L)

Let’s start with measuring urine ketones—a contentious issue! If you’re measuring urine ketones (acetoacetate), remember that these ketones are being excreted, meaning, they’re not being used as fuel in the body. (You are literally peeing them out.) So this isn’t really the best gauge for how you’re metabolizing ketones. Plus, you might notice less of a color change on the urine test strips over time, and maybe even get to a point where there’s no change. This doesn’t necessarily mean you’re not in ketosis anymore; it might mean that your body has become better at using ketones and is therefore wasting less of them in your urine. So rather than being disappointed, you could take this as a good sign. (Keep in mind, though, that many people find the color still does change even when they’ve been keto for years. It might not be dark purple very often, but they’ll see light pink—subtle, but still a noticeable change. And some people who’ve followed ketogenic diets over the long term notice very little lightening of the color. So YMMV.)

That being said, urine test strips do serve a purpose. They’re great to use when someone is new to keto. Seeing that little square turn pink or purple can be a big morale boost and serve as encouragement to stick with this way of eating. It’s visible proof that their body has made the switch from “sugar burner” to “fat burner,” and they’ll feel like they’re on the right track even if they haven’t lost any weight or had other noticeable benefits yet. (This can be especially motivating for the newbies because most people will see pink or purple on these things within about 2-3 days of starting keto if they’re brand new to it, and that might precede fat loss, reduction in joint pain, clearer skin, and some of the other effects of going low carb. So it can be a positive reinforcement before anything else starts to change.)

For interpreting blood ketones, there are a couple of pitfalls. Ketones are a fuel—just like glucose and fats. The level of ketones measured in the blood reflects the dynamic between ketone production and ketone utilization. Here’s a real-world example: well-trained athletes and people who are very metabolically healthy might not see high blood ketones because their bodies are using the ketones at nearly the same rate they’re being produced. This means the ketones don’t have a chance to build up in the blood. Instead of interpreting this as someone not being able to get into “deep ketosis” and thinking it’s a problem, we could just as easily see it as something good: their bodies are efficient at using the ketones.

People with hyperglycemia have high blood glucose because their cells aren’t taking up and using glucose, right? So the glucose just lingers in the blood. But for some reason, when it comes to ketones, we automatically think that a buildup in the blood is a good thing. (I’m not saying it’s not a good thing. I’m just pointing out the contradiction. Again, I fully recognize that there are medical conditions that might require a certain sustained level of blood ketones. So all I’m doing is raising an interesting point.)

Ah! We have come to the most important part of this post.

There’s an often overlooked but critically important point that rarely gets discussed: free fatty acids.

The body runs on three primary fuels, but we can measure only two of them ourselves. We can measure ketones and blood glucose, but the one that provides the majority of energy in people on ketogenic diets is the one we can’t measure: fatty acids (fats).

There are meters to measure glucose and ketones, but there are no fatty acid meters—at least, not yet. So if you feel great and have good energy, no carbohydrate cravings, your moods are stable, and any symptoms you’ve had in the past remain resolved, but you regularly see ketones at the low end of the range, or perhaps not even in the range of nutritional ketosis at all, there’s a chance your body is humming along just fine on a high amount of fatty acids. So WHO CARES what your ketone level is?

When you’re new to a ketogenic diet, many different cells and tissues will use ketones for fuel. After a while, though, skeletal muscles (like your quads, glutes, and triceps) and cardiac muscle cells (that is, your heart) will preferentially use fats/fatty acids in order to spare ketones and glucose for tissues that can’t use fats, or don’t use that much of them—such as the brain. And if the brain is taking up ketones efficiently, they might not build up in the blood. Plus, evidence is emerging that some ketone production happens within the brain itself: cells called astrocytes break down fats into ketones and then export the ketones to be used as fuel by neurons. (Lauric acid, the predominant fatty acid in coconut oil, seems to be an especially good substrate for this, which is likely why it’s so helpful for Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative conditions.) All of this is localized inside the brain, where none of the home measuring devices can assess it. So if you feel great but you don’t see a high ketone level, trust that your body and brain are doing exactly what they’re supposed to do—taking up their optimum fuels.

Finally, keep in mind that ketones are a product of incomplete oxidation (“burning”) of fats. If you’re following a solid ketogenic diet, getting plenty of exercise and good sleep, but you rarely see high ketones, it could be that your body is better at completely metabolizing fatty acids, so there aren’t a lot of ketones being generated in the first place.

If you want to nerd out on the biochem of how this works, read on. If you are terrified at the mere thought of nerding out on the details, skip this section and start back up again where it says “How to Proceed.” I encourage you to put on your proverbial galoshes and wade through this as best you can, though. Even if you don’t grasp all of it (frankly, I don’t grasp all of it either!), you’ll be able to pick up a few things here and there. And the reason I wrote this post is because I am tired—so tired—of hearing people make outlandish claims about ketones and ketosis when they lack even a rudimentary understanding of the pathways and mechanisms involved. Don’t be one of those people.

Ketogenesis: How and Why Do We Make Ketones?

Also: Fat Adaptation versus Ketosis

(A crude diagram of what I’m about to describe is below, so don’t worry if you don’t understand this just yet. It’ll make more sense when you see it.)

Ketones are produced when the amount of acetyl CoA produced from beta-oxidation of fatty acids exceeds the amount of oxaloacetate (OAA) available to keep the Krebs cycle going. If you have enough OAA available, you’ll fully metabolize the fatty acids and produce ATP from them. (“Hepatic ketogenesis is a spillover pathway for β-oxidation-derived acetyl-CoA generated in excess of the liver’s energetic needs.”) OAA can come from many difference sources. Glucose is one of them. (Glucose is converted to pyruvate, and pyruvate can be converted to OAA.) This is where that phrase “fats burn in the flame of carbohydrate” comes from. But fats don’t burn in the flame of carbohydrate; they burn in the flame of OAA, and guess where else OAA can come from? Amino acids! Yes, amino acids, from the protein everyone is so damn terrified of eating on a ketogenic diet. Amino acids can be used as substrates for pyruvate synthesis or OAA synthesis, or if they are converted into glucose via gluconeogenesis, they can be made into pyruvate again. It’s all very neat…lots and lots of overlapping pathways. (Good diagram of all this on the first page here.)

Either way, when you have enough OAA to keep the Krebs cycle running in the liver, it keeps running. And in running, it uses acetyl CoA derived largely from fats. So you are still “burning fat.” You are still “running on fat,” even if you are not generating lots of ketones. This is why you do not need to be on a super-strict ketogenic diet to be fat-adapted or to lose body fat. Capice? You need to keep carbohydrate low enough that your body is forced to turn to a different fuel source (fat), and you need to keep insulin low enough that your body can use this other fuel source. (Remember, insulin inhibits lipolysis.)

Most of us can accomplish this very nicely on a diet that is low carb, but not necessarily super-strict ketogenic. It’s also why protein might “kick you out of ketosis,” but for most people, this is not a problem, because the reason you are not producing high ketones is because the amino acids from protein (and glucose released from the liver under glucagon signaling from protein ingestion) are providing your liver with enough OAA to keep burning the fats, so the fats are not “spilling over” into ketone production.This explains why ketones are said to result from the “incomplete oxidation of fatty acids.” You are still oxidizing them; you’re just not sending them into the Krebs cycle in the liver. Instead, they will be made into ketones and exported from the liver into the circulation to be taken up by some other tissue’s cells, where they will be converted back into acetoacetyl CoA, then back into acetyl CoA, and used in the Krebs cycle in that cell. We cool now? (The liver produces ketones, but it doesn’t really use ‘em. It provides this nifty service for other cells.)

|

What you see in this very simplified diagram:

In order to keep the Krebs cycle going, acetyl CoA must condense with OAA. If there isn’t enough OAA to keep the cycle going, acetyl CoA is instead made into acetoacetyl CoA and then into ketones. “Ketones are produced when there is no longer enough oxaloacetate in the mitochondria of cells to condense with acetyl CoA formed from fatty acids.” (Source.) If there is enough OAA, then acetyl CoA—which is still coming from the breakdown of fats—goes through the cycle as normal. You must understand that some of this acetyl CoA came from fatty acids.

You are still “burning fat” even though you are not generating high ketones.

I have to emphasize this point because I saw a comment on Twitter the other day wherein someone said something to the effect of, “If I’m not in ketosis, then I’m storing fat.”

Whoa, whoa … WHAT?

I had already been planning to write this post for several months, but that comment is what got me to finally sit my fanny down and do it.

As I have written about eight hundred times in other posts, you do not need to be generating high levels of ketones to be metabolizing fat. The body does not operate in a binary system where the two choices are:

Just because you’re not in ketosis doesn’t mean you’re somehow not metabolizing fat so that the only other possible destination for it is to be stored. To be honest with you, my dears, I wrote this post partially to try and help people understand how this works, but mostly to save myself from having to read dumb shi stuff on the interwebs that nobody has the patience to try and correct in 140-character installments.

If you need to be on a ketogenic diet to manage a serious medical condition, then be on a ketogenic diet and take deliberate action to maintain high ketones. If you want to lose body fat or improve insulin/blood glucose issues, then keep your BG and insulin low. These two approaches are not the same.

Now, before anyone gets all worked up over this, if you find that you, personally, need to keep your carbs (or your protein) very, very low in order to lose fat and/or maintain a body composition you’re happy with, fine. Do that. But please do not—repeat, do not—scare other people into thinking they are gigantic failures if they’re doing “everything right” and their bloodwork is the stuff of legends, but their ketones stay on the low side.

Chris Masterjohn has a great video on how ketones are synthesized if you want to really geek out. Chris’s video lessons are fantastic, but don’t get in over your head if you don’t care about the real nitty-gritty. I’m linking for the people who might want to dive deep. If you’re doing a low carb or ketogenic diet for fat loss or your general health and the last thing you want is a biochemistry lesson, steer clear!

Remember what I said earlier: it’s possible ketones build up in the bloodstream when other tissues are not taking them up as quickly as they’re generated. As I mentioned, it’s pretty common for highly trained, athletic people to not see high ketones. Perhaps this is because they are fully oxidizing the fats, their other tissues are taking in the ketones efficiently, or both.

Whatever the reason, it sure ain’t because they’re “doing it wrong.”

To sum up: It might be helpful to measure ketones if you are using a ketogenic diet to manage a specific health concern. It’s less crucial to measure if you’re aiming for fat loss or overall wellbeing, but even then, there are valid reasons to measure, particularly if you’d like to see if there’s a correlation between your ketone levels and your mood, energy levels, food cravings, etc. The important thing is to understand the numbers you see. And the good news is, once you establish whether there’s a correlation between your ketone levels and good things happening to your body and brain, you don’t have to keep testing. Once you know which foods and activities work best for you, you can stick to them unless and until they stop working so well. (It’s true, folks. Even on keto, our bodies change, circumstances change, and what worked like magic at one time might not be right for you at some point in the future. Be flexible and open to change.) You can check in now and then with your meter just to see where you are, but you don’t need to test every day, forever.

I must stress, however, that I am not a fan of people measuring ketones if their goal is fat loss. Why make this more complicated than it needs to be, especially if you’re going to freak out if your ketones are “only” a certain level? I wrote this post to explain how to interpret the numbers, not as an endorsement or encouragement for everyone to measure. If you want to measure, have at it, but please do so with a desire to understand what the data are telling you, and take a deep breath before you post an anxious and fearful cry for help on your favorite keto forum.

In a study run by the people at Virta Health (of which Dr. Phinney is the founder and Chief Medical Officer), type 2 diabetics who followed a ketogenic diet for 10 weeks saw impressive reductions in HbA1c, fasting glucose, triglycerides, and body weight. (Doesn’t look like they measured insulin; it’s too bad; that would have been nice to see.) Not only that, but from the study:

“The majority of participants (234/262, 89.3%) were taking at least one diabetes medication at baseline. By 10 weeks, 133/234 (56.8%) individuals had one or more diabetes medications reduced or eliminated.” (Including insulin!)

“Baseline HbA1c level was 7.6% (SD 1.5%) and only 52/262 (19.8%) participants had an HbA1c level of <6.5%. […] At follow-up, 47.7% of participants (125/262) achieved an HbA1c level of <6.5% while taking metformin only (n=86) or no diabetes medications (n=39).” (This is a big improvement. HbA1c <6.5 is no longer classified as diabetic. A1c between 5.7 and 6.4 is "pre-diabetic," so many of these individuals were still pre-diabetic, but that is movement in the right direction for sure.)

I am sharing this with you because these participants were issued blood ketone meters for the study, and the mean BOHB level during the 10 weeks was… wait for it… 0.6 mmol/L.

Now, granted, these subjects were overweight adults with T2 diabetes. The goal was not to win the CrossFit Games or to compete in a physique competition. Some of these folks were in pretty bad shape, metabolically speaking. The goal was fairly modest: to evaluate “whether individuals with T2D could be taught by either on-site group or remote means to sustain adequate carbohydrate restriction to achieve nutritional ketosis as part of a comprehensive intervention, thereby improving glycemic control, decreasing medication use, and allowing clinically relevant weight loss.”

Well, by those criteria, the subjects did stunningly well. If you are so inclined, check out the full text and take a look at the chart on p.8 – THAT IS AMAZING. People decreased or eliminated meds left and right, including insulin. NICE! And all that with ketones at a whopping 0.6. (As for the cases of increased doses of meds or people adding new meds, I’m guessing that was likely because people eliminated more powerful or more harmful meds and switched to milder ones — because they didn’t need the more powerful ones anymore.)

The changes from baseline to the 10-week mark are pretty damn impressive. For many of the subjects, A1c, fasting glucose, body weight, and some of the other parameters were substantially reduced from baseline, but were still high at the end of the study. As I said, many “improved” from T2D to pre-diabetes, but it was only 10 weeks – less than 3 months’ time. This is actually remarkable. Think what could happen given more time. (Funding a study can be a huge undertaking, so the fact that they were able to finance it for as long as they did is great.)

Would these people have had even better results if their ketones were higher? *Shrug.* If so, I would posit the higher ketones would have been a result, not the cause, of improved glucoregulation and insulin signaling. All I’m saying is that they achieved pretty damn impressive results with a mean ketone level barely within the range for nutritional ketosis. (Some subjects likely were higher here and there during the study duration; only the mean is provided.)

Eat the things you know you can eat; avoid the things you know you should avoid, and the improvements will come – with or without ketones.

P.P.S. I am considering starting a Patreon account to fund the many hours of otherwise unpaid time that goes into posts like this. Since I haven’t done that yet, if you found this post or some of my others valuable, please consider making a contribution to this effort via PayPal. There’s a button in the sidebar on the right on my site, or you can simply use your PayPal account (I think you can sign in as a guest if you don’t have one) and send to my email address: [email protected]. Any and all amounts are welcome and appreciated. If you can only spare $2, that buys me a cup of coffee, which I assure you, is a great contribution to my writing efforts!

Remember: Amy Berger, M.S., NTP, is not a physician and Tuit Nutrition, LLC, is not a medical practice. The information contained on this site is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any medical condition and is not to be used as a substitute for the care and guidance of a physician. Links in this post and all others may direct you to amazon.com, where I will receive a small amount of the purchase price of any items you buy through my affiliate links.

OnKeto.com is a news aggregation service that brings you best of world articles to you for your consumption.

Author: Amy Berger

Author URL: https://plus.google.com/112079352426148614740

Original Article Location: http://www.tuitnutrition.com/2017/09/measuring-ketones.html